PhotoCredit: Yelena Odintsova.

I couldn’t help but scroll back to the image I just passed on Instagram. I was looking at a graphic of a brown sole coming down on, as if wanting to stomp and crush, a person. ‘BEYOND INDIVIDUAL BLAME’, read the graphic, with a footnote-like message at the bottom, presenting a fact about the fossil fuel industry’s coining of the term ‘carbon footprint.’ I was immediately struck at the power of the message, thinking ‘Wow!’

I sat down with Anais Reyes and Dislahnie Perara, two staff members at The Climate Museum who worked closely on the Beyond Lies campaign, to learn more about the ideas behind the program.

“The response you had is the response we’ve been getting a lot: shock and basically, checking everything you thought you knew, and the response after that initial response can go a lot of different ways,” Anaies Reyes told me in the interview. Reyes is the Senior Exhibitions Associate at The Climate Museum, based in New York City. It is the first museum in the United States to focus on climate change and action, and was founded by Miranda Massie in 2015 after Hurricane Sandy.

“What makes the museum really unique is [its] mission to inspire action around the climate crisis. We think of our constituency as two-thirds of Americans who are worried about the climate crisis, but are yet to take action, including talking about it with family and friends,” Dilshanie Perara, a postdoctoral fellow in Climate and Inequality working across programming at the Museum, mentioned in the interview. Perera went on to say that “throughout all their programming, the aim is to provide pathways for thinking of ways to take action to engage in community building, and can even mobilize your communities.” Thus, the individual is an active community member when visiting the museum as opposed to a passive visitor.

Both Reyes and Perera worked on the Beyond Lies campaign with other team members and Mona Chalabi, data journalist and illustrator. Mona Chalabi’s work is extraordinary, to say the least, introducing work that has a sounding alarm attached to it, almost drawing you with the colors and illustrations to pay attention. The Beyond Lies campaign is no different.

“[The campaign] came about in the midst of COVID19. We had transitioned into online programming, but as a museum, it’s very important to us to create some sense of a communal space for people to gather and share an experience. We had to create some kind of programming that connected people to action, to collective action and empowers people, but it had to be COVID safe, and applicable to the moment, political and otherwise, and so, we wanted to do a project that could be outside, public, [and] reaching diverse communities,” said Reyes. “It was a combination of wanting to talk about the fossil fuel industry because we started research of the industry and misinformation two years ago, and it was something we wanted to do in person. It was a different team member that recognized and suggested Mona [Chalabi]. She’s so good at addressing social issues with numbers and illustrations, and it’s all understandable and accessible. It’s a little different [from] what we’ve done before because it’s not really an exhibition or a public art project in the way we’ve done in the past. The way we’ve talked about it with Mona and some of the students who worked on this was putting these posters up places, engaging with it and having conversations – that’s creating the art. We’re really pleased with it.”

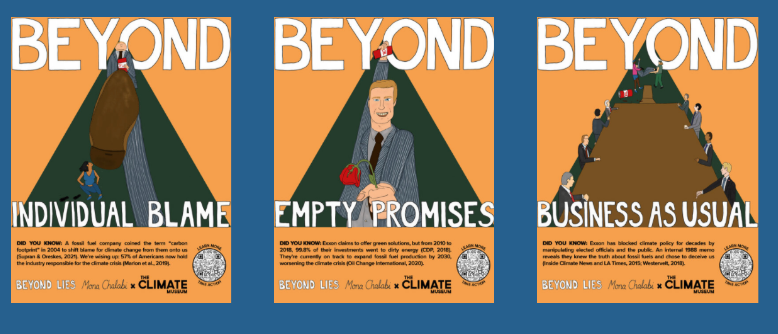

Image: Beyond Lies from beyondlies.org

The three posters each speak to research on the fossil fuel industry’s misinformation throughout the past several decades.

“Each of the posters represents a distillation of so much research we all did on the team because we knew we wanted the campaign to be centered on how the fossil fuel industry has been lying to the American public for decades, the ways the industry has been able to intervene in American politics, and being able to expose these lies and convey them with the truth. It required looking at different kinds of datasets and getting through the history of fossil fuel disinformation, being able to see how they’ve been able to change their messaging in relation to the news and public opinion. Mona has an incredible ability to visualize complex data. The themes emerged from this process – going through different kinds of data, stories and coming to the facts that we wanted to tell, that we, ourselves, found emotionally resonant,” Perera said.

From coining the term ‘carbon footprint’ to shift the blame from corporations to individuals to making empty promises to going about our changing world as ‘business as usual’, the campaign draws on the work of investigative journalists and academic researchers. Thus, the campaign appears to be an embodiment of the intersection between data science and art.

“It reminds me that everyone has a place in this [campaign]. You have the academics writing the research and collecting the data. Then, we come in to help communicate that day, and then, we work with the artists, who can translate that into an image or some kind of visual or artistic intervention. The journalist, then, comes in and talks about it and connects it to the public sphere. There’s all these different people coming in and leaving their mark on this project. Even the students that we work with, that come in to do the actual foot work of going into their communities and talk to their local store owners, the YMCA, their family, friends and schools,” said Reyes. “People understand climate change and activism in a certain way, but it’s all connected and applies to everyone and everyone can have a part. That’s why we talk about civic action as a solution.”

Each poster has a QR code in the right bottom corner that links to action steps, from printing and distributing the posters to calling your local representative to demand action on climate change. “Through the conversations we had with Mona, this isn’t the boundary of the piece. It keeps going beyond the poster itself,” said Reyes.”

Perera said, “We like to say that one of the goals of the campaign is to revoke the fossil fuel industry’s social license to operate. This is part of what journalists, academics and artists are doing already. There’s a whole list of people that were experts we worked closely with, taking their insights and really being able to push back against these claims [from the fossil fuel industry].”

“Part of the reason why we did this is because it was a conversation that was expanding the climate vanguard. It hadn’t yet reached the public. We knew and expected that there would be a push and pull. This is the way things are, but it doesn’t have to be the way they [stay],” Reyes added.