As I stepped out of the airport in Siem Reap, Cambodia, I was immediately greeted by hot and dry air. I was drenched in sweat within 10 minutes. As I waited for my Grab taxi, meter taxi drivers approached me repeatedly, saying, “Bong! taxi, same price Grab!” I didn’t know how to respond appropriately. I simply smiled and bowed, unsure whether that was the right thing to do (I hoped the travel bloggers didn’t mislead me). Feeling slightly out of place, I walked toward the parking lot to wait for my ride.

My driver eventually arrived, kind and charismatic in his old brownish gold Lexus. “First time in Cambodia, Bong?” he asked. I smiled, laughed, and said yes. From my outfit, it was probably obvious that this was my first time here. As we drove into the city, I took in my surroundings – the sandy-brown roads, the towering trees, and more motorbikes than I had ever seen in one place. One motorbike carried an entire family, my jaw dropped but quickly turned into a smile, as the mother caught my eye and smiled warmly. In that small moment, I thought to myself, “I think I’ll be okay here.”

When we arrived at the apartment, the driver smiled and said goodbye, again calling me “Bong.”

Over the next few days, I came to understand what “Bong” meant. It’s a Khmer term of address – gender-neutral and used for someone older than you or when someone’s age can’t be assumed. As a foreigner, I began to hear this word used for me often. I started using it too. Being called “Bong,” and calling others the same, gave me a subtle sense of belonging. The word created a space in which I wasn’t marked as an outsider – at least not immediately.

There was something transformative in this. I didn’t feel like a stranger. I felt seen. The term “Bong” gently collapsed the divide between local and foreign. It did not erase my difference; my skin was still visibly different, so was my large form. I was different but the word extended an invitation to participate. To be included without pretending to be the same.

Language, in this way, was not merely a functional tool for communication, it was a bridge. In being addressed as Bong, I was neither exoticized nor excluded. I was folded, however briefly, into a shared world. That single word softened the barriers between “us” and “them.” Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once suggested that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Perhaps when we answer the questions of how to create spaces with a sense of belonging, we can turn to language to help us expand our worlds.

During my time in Cambodia, I was not only a tourist or an observer – I was Bong Nolo. I did not lose who I was, but I became part of something larger. Even when I didn’t quite understand what was happening around me and I felt walls build as I would get threatened by different ways of living. The word would bring me back.

Édouard Glissant’s idea of relation in cultural identity comes to mind here, true belonging, he argued, doesn’t come from sameness, but from the recognition of difference as part of a shared human experience. In Cambodia, I learned that to belong didn’t mean to dissolve into sameness. It meant to be invited in as I am. This difference wasn’t always celebrated or liked but it was acknowledged through curiosity and small inquiries about who I am.

Belonging, I discovered, isn’t a threat to individuality. It’s an invitation to discover how you can exist in new spaces without becoming invisible or inauthentic. As philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah often emphasizes, identity is not about fixed essences, but about how we live and relate with others, always in motion, always negotiated. In the negotiation with Khmer people, the bargain was simple. I was Bong first and then all other parts of that made up my identity; this eased the differences we had.

Language, in this way, was a subtle and powerful social technology. It binded worlds and mending strangers together. The word “Bong” gave me a glimpse into a world where belonging didn’t demand that I change who I was, only that I be open to who I might become to others.I was Bong, the customer at a restaurant, Bong a potential sister to my partner’s siblings, Bong the lady browsing dresses at the market. The same person, seen through different relationships and respected in all.

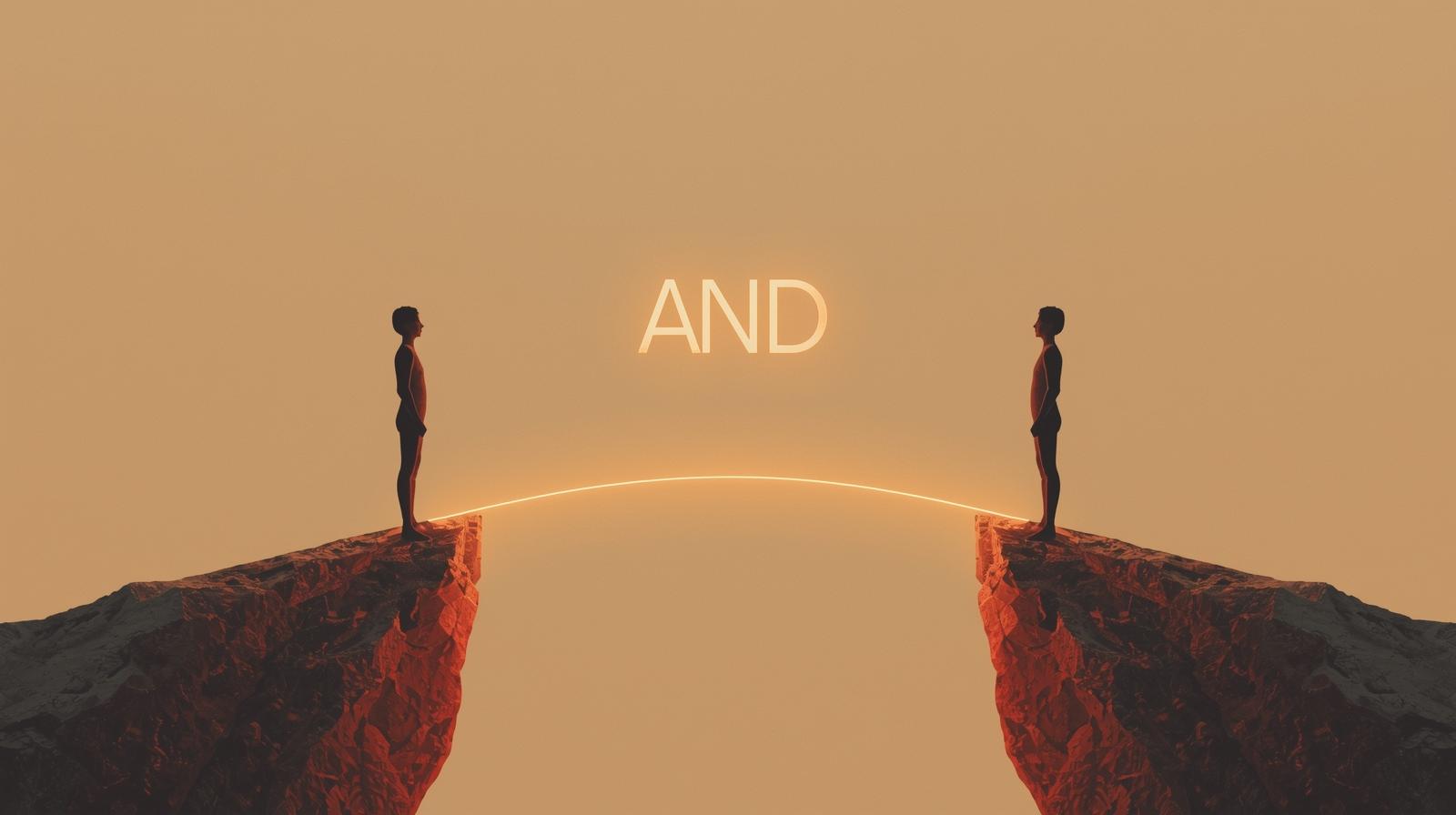

How differently would you speak to a stranger if you saw not only what your eyes show you, but also who they could become in relation to you? Your neighbor, who looks nothing like you, might become a reliable guardian to your children. How would that change the way you choose to interact? Beyond Khmer, the English word “and,” a simple three letter word, holds the same incredible power. In a world full of differences, holding firmly to “and” means choosing to bridge rather than break. You are not from my country, and you are my neighbor. What then might I cultivate in our relationship? That simple “and” softens the edges between “me” and “other,” creating a space where identity is fluid and relationship precedes categorisation. This simple ‘and’ invites us to live with complexity, hold contradictions, and remain open to change within ourselves and others.

So, when we talk about othering and belonging, perhaps these are invitations to explore the “ands” within ourselves and others, the many layers resisting simple categorization. As Helen Bevan and Goran Henriks describe change and encourage us to think about how to be “a resource for change” in our communities by embracing the evolving multiplicity in each person.

After reading this, I invite you to imagine a floating “and” hovering above the heads of those around you. It might feel strange at first but please try it. The truth is whenever we look at people we already make assumptions both informed and unfounded assumptions. We cannot stop this entirely but we can interrupt it with that simple “and” by choosing curiosity about what comes next. Think back to the last time you chose breaking over bridging with someone you did not understand. If, in that last conversation you chose ‘and’, what new story might have begun?